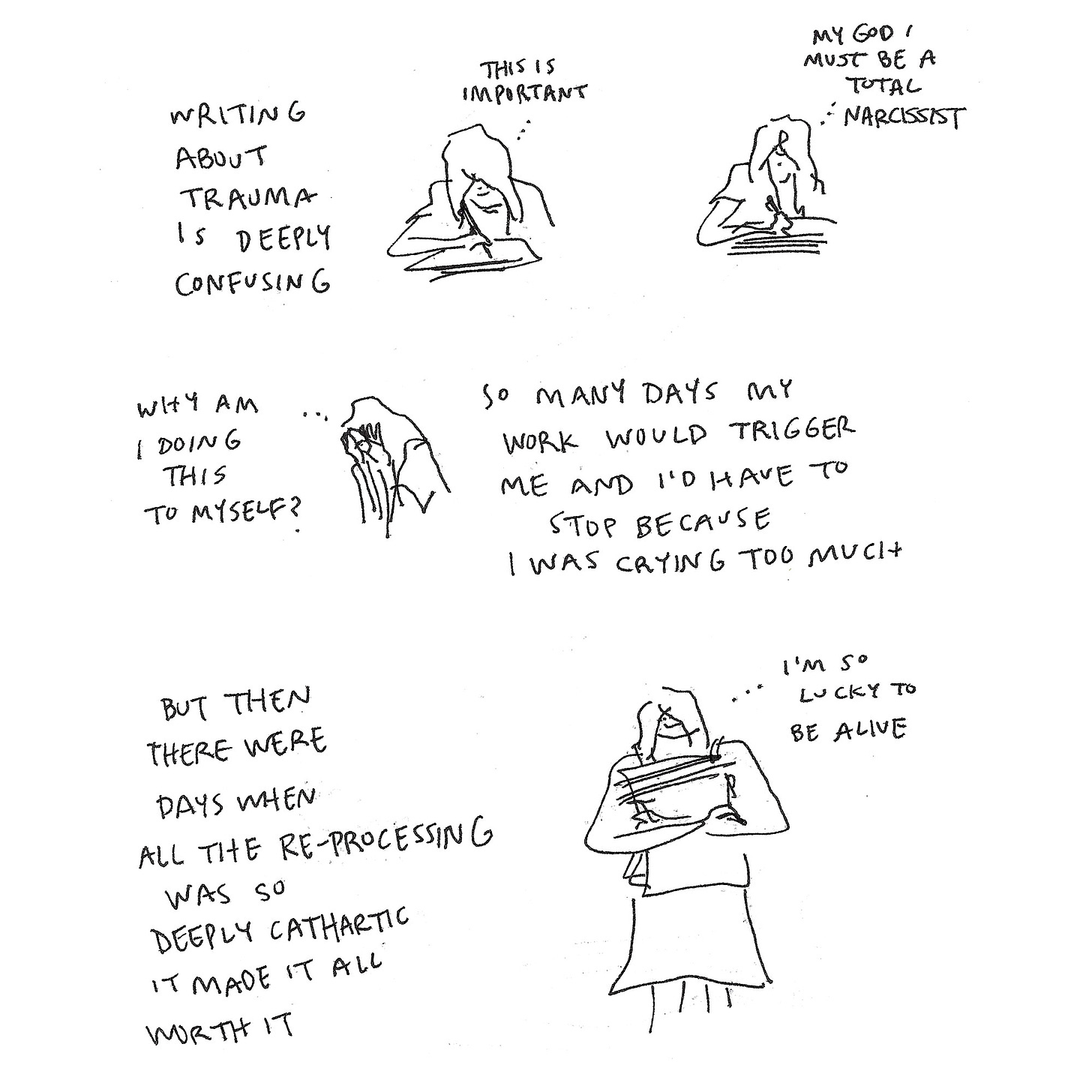

For years I could barely write a page. I thought I was becoming a virtuoso of smallness while the grief, which is wordless, occupied an ever-greater volume.

– Sara Manguso, “Perfection”

Imagine you’ve asked someone to wrap you head to toe in cellophane—tight, like a mummy—then roll the whole thing in duct tape and tie it up with rope.

After lying there for several years, acclimating to your new shape, muscles atrophying, you no longer can tell where your body ends and the cocoon begins. Your arms and legs—and all your senses—have become theoretical, not real.

Now try to get out of it.

Wiggle your enfeebled fingers and toes, trying to remember what they are. Let them explore the small field around them until they find purchase and make a tiny, hopeful tear in the plastic. (Or is that your leg?)

Wiggle and tear, wiggle and rip while a voice yells insults at you about how poorly you are doing it, that no one is waiting for you to get out, that you have been forgotten and may as well stay in your cocoon.

The metaphor is a physical one, but it’s exactly how the intellectual mechanics of writing a memoir feels to me. You have to see the shape of your life — or a part of it anyway — and to do it you have to remove yourself from your husk and step away. But the husk is you.

It’s somewhat of a Zen koan. See inside your own eyelid and report back.

Let’s assume you successfully remove yourself from the husk. Now you have to sort through All Its Wildly Important and Beautiful and Overwhelming and Awful Wonders, and choose, say, 10 moments that tell the story you wanted to tell.

As the frogs say: Gulp.

Get ready for metaphor #2:

If you’re an artist (or maybe any sensitive person), your life might seem to you like a wildly important film on fast-forward that repeats again and again, each time getting several scenes longer as you get older. The last scene is the present moment, and then it starts over. You carry the entire movie with you into the present moment.

Most of us have to close the door on this eternal movie just to get anything done (or not feel overwhelmed with longing, grief, anger, nostalgia). To write a memoir is to stay in the room and watch the cursed film over and over, pausing and rewinding, trying to find the stories — out of the film’s thousands of possible stories — that you think best tell the overarching story of the memoir, which is contending with something you are only JUST NOW ready to face fully, and which you still don’t completely understand. That’s why you’re writing a memoir in the first place: To understand what happened. (Who gave you this counterintuitive, awful job?)

And that’s assuming the film is even reliable. Or intact. Whenever I re-read my old journals, it’s almost unbearable at times—the bald self-deception!

“I need to relax—why the hell can’t I just relax??” (My diary at 20, while living with a man I was addicted to and couldn’t stand.)

It’s hard to sit in the room with the film of yourself betraying yourself, and then decide whether or not to include it in the work. To write a memoir is to be a ruthless editor of your own past. What parts of this ongoing, devastating, and Most Important film should you leave on the cutting-room floor? I chose scenes that wouldn’t leave me alone.

My mother bending to pick up a crab claw on the beach, the salty wind blowing our hair as she opens and closes the claw like a mouth, doing Señor Wences: "You want to talk to my crab?” she asks in his Spanish accent. “S’alright? S’alright.”

Me sitting on a playground swing, telling the kids at my new school that we left my mom because she was a drug addict and a slut, trying on these words, this anger. The scandalized kids run away, and I sit alone making my right hand into a puppet, imagining two dots beneath my knuckle for eyes, and sliding the sad mouth of my thumb up and down. “Mom,” the puppet cries. “Mom. Mom.”

Wanting and rejecting. Reaching out and being denied. If these were the constant currents beneath my life, then of course they’re the currents that compel my work, and the way I come to the work.

I meant this to be about avoidance. I was frustrated with the Rube Goldberg devices I set between myself and completion of the work, all my diaries I think I have to read and annotate first, all the furniture-moving I have to do to “free up the creative energy” in my space, the 13 open tabs I need to finally read and process and close before I can think clearly.

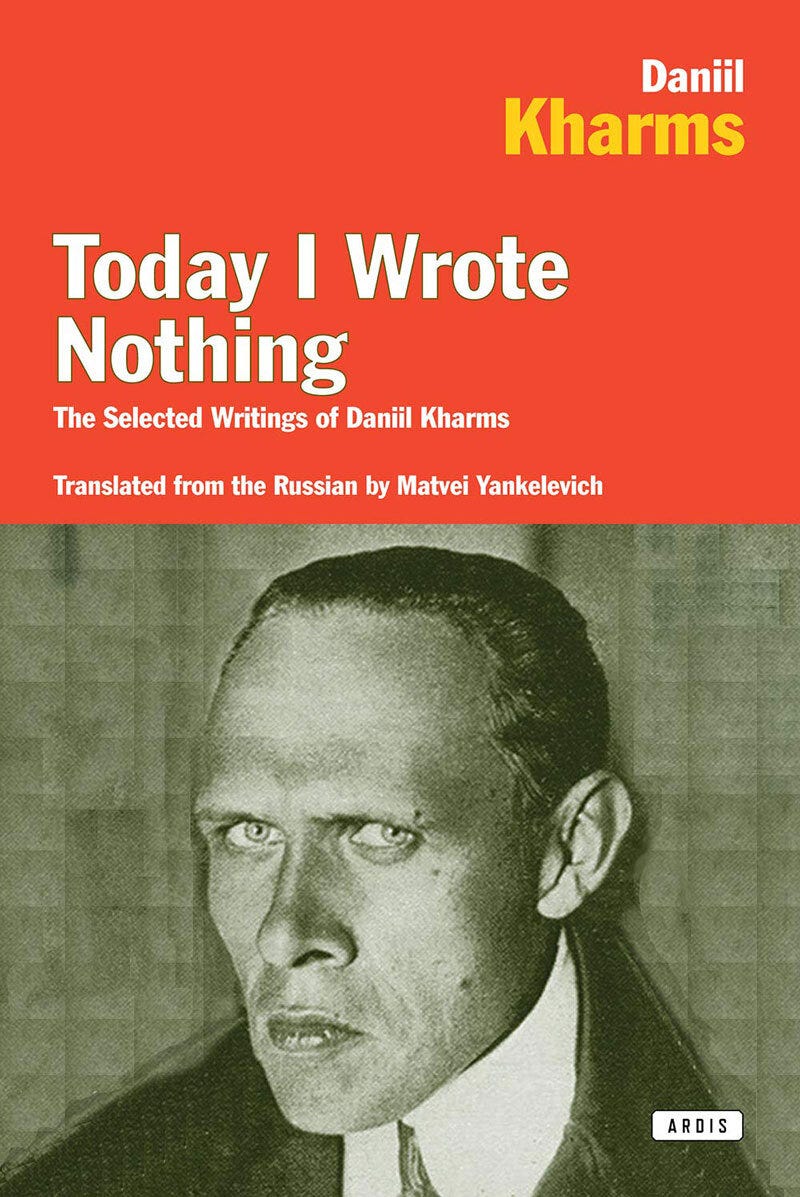

Nothing written for so long. Begin tomorrow. Otherwise I shall again get into a prolonged, irresistible dissatisfaction; I am really in it already. The nervous states are beginning.

And gods, the amount of time it takes to write anything that might live up to my potential!

Oh that I could swallow a pill that would convince me that people want to luxuriate in an indulgently long, beautiful, and neurotic haze with me. I can’t entirely blame my abandonment issues—there’s a well-documented disdain for memoirs, especially memoirs by women, even by other women memoirists.

(For an antidote, I turn to Melissa Febos’s “The Heart-Work: Writing About Trauma as a Subversive Act”.)

"When we speak, we are afraid our words will not be heard or welcomed. But when we are silent, we are still afraid. So it is better to speak.” – Audre Lorde

Those of us who grew up reaching out and being rejected, having sometimes and starving sometimes, will want to avoid writing our memoirs as much as we long to write them. I used to torture myself about this, but I’ve learned something: Avoidance is one half of the whole motion. The other half is advancement. I avoid until I feel an anxiety that compels me forward, even a little. And that little advancement feeds further advancing for days.

Avoid/advance/avoid/advance. Over and over, until I had a 300-page book.

There can be peace in it, like the ebb and flow of the tide. The ebb draws the sea into itself, gathers what stones and shells it can, then offers them back, changed.

Sometimes I tell people “I’m working on a pearl,” meaning an irritant is gumming up my works and I don’t know what it means yet, and I can find out by writing, yes, but I can also find out by not writing. Not writing can be better because once I start writing, I become a little committed to the idea and can no longer accommodate other ideas that might complicate and enrich it. If I put my old diaries down in disgust and shame, and then walk around with that grit of self-betrayal and shame in my oyster, not writing, just working it around in my body, I can produce something resilient and beautiful about our capacity for self-betrayal and shame.

Not all avoidance is avoidance, I’m saying. Sometimes avoidance is advancement.

Much already has been written (or memed) about late capitalism’s effects on art; about how to move slowly and try to make meaningful and lasting art when it feels like we’re on the factory floor, being watched from above, punished or promoted based on output.

Instead of repeating those things here, I’ll end with one of my favorite Mary Oliver poems, which I hope will underscore your periods of ebbing and pearl work:

Softest of mornings, hello.

And what will you do today, I wonder,

to my heart?

And how much honey can the heart stand, I wonder,

before it must break?This is trivial, or nothing: a snail

climbing a trellis of leaves

and the blue trumpets of flowers.No doubt clocks are ticking loudly

all over the world.

I don’t hear them. The snail’s pale horns

extend and wave this way and that

as her fingers-body shuffles forward, leaving behind

the silvery path of her slime.Oh, softest of mornings, how shall I break this?

How shall I move away from the snail, and the flowers?

How shall I go on, with my introspective and ambitious life?

LMK if you’re working on a pearl right now. Also, James Baldwin has been there.

Oof. Are you reading my mind again? I jumped into a chapter I have avoided for too long today and good grief the crying I was also avoiding just walloped me into a wet towel. Yet I kept going for a solid two hours. Advancement! I love your math. (and you) xo

Brilliant.